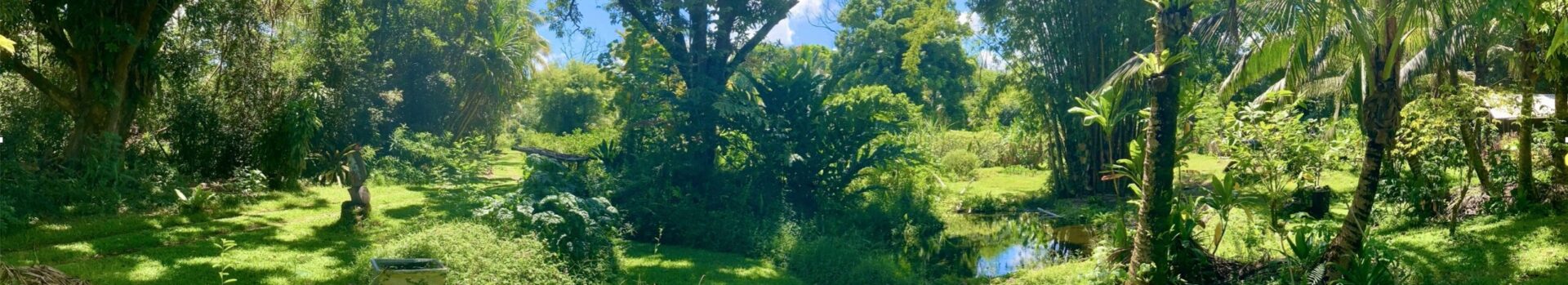

Panax (Polyscias guilfoylei) is a hedge plant that we’ve been familiar with for years. Our friend Wade at Mālama ʻAina Permaculture uses border lines of closely spaced panax to great effect, as a support for field fencing to keep feral pigs out of his property. We’ve know that we want to supplement our metal perimeter fence with a vegetation-based pig barrier as an additional deterrent, especially because the metal fence will inevitable break down. We attend to the small amount of panax we have growing, and occasionally take cuttings to spread throughout our fenceline, but it will be awhile until we build up enough stock.

Enter our good friends who just bought a small, minimally-developed property some miles south of here. Their property is bordered by many mature panax trees which they intend to replace with podocarpus, a more fully-leaved and attractive visual barrier plant. We asked them if we can harvest the panax and they said, “Yes!”

So, we took our trailer, saws, and loppers, and harvested a full load three weeks ago. We decided to plant it along the unfenced flagpole section of our driveway, both to delineate the driveway and to potentially serve as a pig barrier, since the wild pigs often turn up the turf in that area. We’ve been somewhat reluctant to plant the area, because some kind of “pig protection” is required (small fencing rings or encircling boulders) around each plant. But, that is the area where we intend to plant 8-10 clumps different bamboos we’ve acquired, waiting patiently in the nursery.

That first batch of panax I planted at a 9″ spacing. The plant has a marked vertical growing habit, and when it does branch, the secondary branches also shoot up. We brought home material that ranged from about 3″ to 3/4″ in diameter, and 3-7′ long. One just lops the larger poles into smaller planting sticks of at least 32″ length, preferably with a growing tip. We had previously marked the border every 50′ with gliricidia (another stick-culture fencing tree), so I just used concrete stakes to pull a string 6″ in from the border, to allow the panax to gain girth without encroaching onto the neighbor’s land. Then, it was just a matter of working along with the oʻo bar (metal digging stick), eyeballing every 9″ and creating a narrow post-hole to insert the panax pieces into. I soon developed a rhythm in which I selected panax pieces according to the depth or angle (sometimes subterranean boulders caused the bar to lose plumb) of the hole, to best create the living palisade.

Palisade, you might ask? Traditionally, this meant a row of closely placed, high vertical standing tree trunks or wooden or iron stakes used as as a fence for enclosure or as a defensive wall, but in permaculture we can grow our wall and avoid the shortcomings of dead materials which inevitably rot.

On a different–but related–topic, just last week we finally decided to re-home our final two hens. We kept them free-range, and they were just causing too much damage to our delicate plantings, without yielding very much in terms of eggs. So sadly did Jasmine (our chicken-whisperer) say goodbye to Chiquita and Wild One, taking them to join our good neighbor Emily’s flock of three. The silver lining is that we can focus on building up our Zone 1 garden without needing a chicken exclosure first. Also, it gives us renewed inspiration for implementing our rotating paddock poultry design, requiring? You guessed it, living palisades. Jasmine put two and two together about the opportunity with all of this panax available, so our second load has gone exclusively into chicken fencing.

The design calls for a series of paddocks along the periphery of the property, between the boundary metal fence and the interior areas where almost all the human movement (pedestrian, bicycle, automobile) takes place. We have already been planting these areas into chicken fodder plants, and will diversity them even more. When ready, we’ll raise up a batch of chicks and train them on jungle food. Once a mature flock, they’ll be introduced to the first paddock, in which they’ll pasture (with supplemental food like kitchen scraps and coconut meat brought to them) until the forage is appropriately s

et back. Then, through a bamboo gate (yet to be designed), they’ll be led to the second paddock. They will roost in a lightweight bamboo henhouse on wheels that can be moved from paddock to paddock.

Panax is an excellent example of stacked functions. The primary function of chicken containment will be achieved by eventually filling in the panax to a 4″ spacing, or by adding a secondary row of lower barricade plants such as katuk or ofenga. The secondary row can go either to the inside or the outside of the panax, depending upon whether it yields human or chicken fodder. Several secondary functions are also met, including a visual (and, somewhat, auditory) barrier between us and the neighbors; a trellis for vining crops like perennial beans, air potato, chayote, or even cucumber; and chop and drop biomass production for forming mulch rings around adjacent crop trees.

With the mass of panax just put into the ground at either 9, 12, 18, or 24″ spacing, constituting about 750 linear feet of eventual palisade, we should be able to abundantly source our own propagation material in about 12-18 months. We’ll keep you posted on the progress of this project, and we hope to be rotating chickens and ducks within two years!