(an imagining of our future community and land)

It is 2028 and I’ve found my land and my community! We are 20 adults and 8 kids of various ages who found the perfect spot 7 years ago. This land already came with quite a number of bearing fruit trees, a few livable, turn-key structures and enough infrastructure to get us started. But we’ve really put a lot of work in over the years to make it the sanctuary it is today.

What can I say? We ended up together through our insistence that there was a better way to live on this planet. We came together with the understanding that our relationship to the land and all her inhabitants would be nourishing, that we would want to give back more than we take, that industrial culture is killing the living world and that any culture based on extraction and living beyond its means is inherently unsustainable. We entered into this community vision with eyes wide open, welcoming the ebbs and flows of the sun, rain, and wind; they imprint and inform our daily patterns, they guide us towards new and traditional ways of living. We embrace the beautiful limitations of human-scale living. We humbly use our creativity to design harmoniously when needed. We are committed to relearning how to live collaboratively and intimately—to share, respect, and value one another equally.

There are a variety of people here with an interesting blend of skill sets: we have a doctor, a dentist, an herbalist, several permaculture designer/gardener/foody types, a few scientists, and some artists and musicians. We have a realtor and some business types who have run nonprofits, written grants, and/or were once engaged in the financial sector. There are some folks with backgrounds in raising animals, and others who are mechanically-oriented, able to fix engines and machinery, and creative about alternative technologies. We’ve got 3 folks here who are pretty good woodworkers, a handful of rewilders with different interests (tracking, birds, mushrooms, wild plant medicines, etc…). One of the most indispensable skill sets we are lucky to have here is process-work, which supports the social health of our community from conflict resolution and communication skills to counseling.

Many of these folks are not just one thing either! Some of us have a multitude of overlapping skills. For one, there are many here who were educators at some point in their lives, teaching classes, workshops, or working in schools or programs in their fields. And most people, motivated by the current planetary crises, have aligned their skills in forms of activism. I’m really impressed with the caliber of people we’ve attracted here!

It’s fun to be around such a diverse group of people because there is always something interesting to do with someone. The other day I went with one of the elders and 3 kids in the community to guerrilla-plant various seeds and keiki in the nearby forest reserve. While we were there she pointed out some edible mushrooms that we harvested to share at dinner and the kids learned how to sustainably harvest them. Since the kids took such a keen interest in their mushroom lesson, they decided to start cultivating mushrooms in at least one of our gardens as our next Keiki in the Garden project.

The other week a group of us artistic-types got together to make stencils with various political messages we plan to spray-paint around town. The same group, inspired by the film Reefs at Risk, talked about the idea of making official-looking beach park signs to mount at various locations telling people their sunscreens are prohibited from being used at the beaches in Hawaii and that they will be fined heavily if they are caught possessing or using these sunscreens. We thought we could provide free samples of chemical-free sunscreens to beach folks, as well as alternative sun-protective gear—sun umbrellas, woven lauhala visors and wide-brimmed hats, and light cotton tops. Any money we make could go back into a campaign to research and develop natural sunscreen, sourced entirely from our gardens and land. We could then distribute samples of our homemade sunscreen and teach the broader community how to make their own.

Those are just a few examples of some of the smaller activist projects going on, that anyone can help with. There are of course larger campaigns going on too: some folks are working on a documentary film together; there are folks working on a campaign to make sustainable-living legal, from composting toilets to changing laws around living in community. We also have campaigns to shift our islands to food-self sufficiency; development of LFA (Little Fire Ant) biocontrols to wean us off chemical solutions; soil-building/carbon sequestration/forest restoration; Hawaiian sovereignty; and Anti-Monsanto/chemical industry campaigns, to name a few. Each campaign covers such a wide variety of ways to plug in that just about anyone can hop in on the aspect that interests them most.

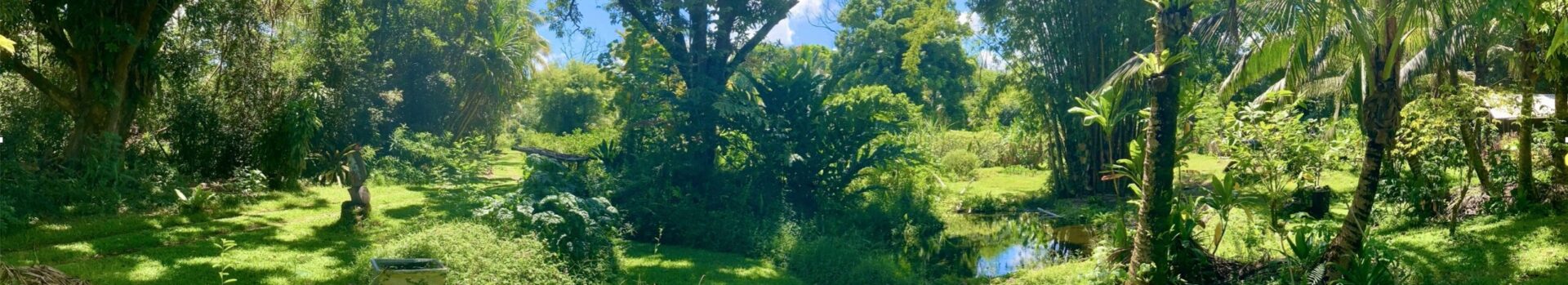

The community sits on close to 100 acres. After the purchase, we spent the first year just observing and experiencing the land through the four seasons before beginning any major development. From this experience, we were able to produce a diverse, comprehensive land design using the principles of permaculture. The plan set aside plenty of undeveloped, wild spaces and forested areas. There is a stream through the land, with a couple of waterfalls. There are lots of places to wander around the land besides the forested areas. We have a few orchards, 3 large ponds, we have promontories with amazing views of the ocean, and of course we have all kinds of nooks to hang out in the various gardens.

We have a group of “eco-artists” who created beautifully landscaped outdoor areas for inspiration and meditation. Not too far from the community center is a labyrinth planted with flowers to draw bees and butterflies. Nearby are living scultpures where the terrain is landscaped to look like figures and faces. There are also trees altered to look like friendly faces with crystals and jewels hanging from their limbs, and a copse of guava woven into aerial living hammocks! Kids and adults alike adore exploring this magical area to daydream, play, and satisfy their curiosity.

Our goal is to eventually source all our needs from the land, including our healthcare. That’s why we designed what we call our Farmacy—a huge garden full of medicinal plants, from herbs, flowers, shrubs, roots, spices, fungi and trees. The handful of people with backgrounds in botany and herbalism host classes to teach us as well as the public about how to make and use these medicines. More of us will need this knowledge as fossil fuel based pharmaceuticals and medical interventions become too expensive or unavailable. Medicines like turmeric, noni, serpentina, ashwaghanda, and aloe are powerful and effective, so we should learn to use them now. We even have a pit outside the garden to make activated charcoal for cleansing.

There are some clever appropriate technologies that have been utilized on the land. Take the water wheel, for example. One of our mechanically-inclined residents, with the help of a team, designed and built a large water wheel from salvaged tongue-and-groove cedar wood. During heavy rains when the stream swells into a raging river, we turn a wheel that shifts a door-like paddle serving to divert water into a parallel canal. The diverted canal of water spills over a short rock face and down onto the “cups” of the wheel. Once the wheel gets moving it can generate electricity, or operate various mechanical drive-band technologies.

We also utilize the simple but effective design strategy of gravity-fed water by collecting and storing rainwater at the top of the property; gravity, rather than pumps, naturally brings water down to the lower lying faucets, showers, and spigots. Aside from the water sources of the stream and the rain, the previous stewards of this land had dug a well. We have not used the well and plan to create a passive pumping technology, (perhaps using a small wooden windmill?) before we do.

One of our woodworkers on the land spearheaded the project of planting a lumber crop with a nice variety of woods. Aside from wood that will make great posts and lintels, we have various wood for carving and wood working, wood for slabs, a variety of bamboos for construction, furniture work, weaving, etc… That’s already been growing for 6 years! Interspersed in various areas of the land are also fiber crops such as cotton, hemp, flax, kapak, palms, and hala, etc… I host workshops every month to teach people ways to make cordage, and yarns, ways to weave, and make fabrics. It’s really fun and useful! I recently learned how to weave Polynesian fish traps; I taught some of the kids how to make them and we plan to try them out in all three of our ponds to catch tilapia and fresh water eels.

Our community has an affinity for creative ways to use local materials and we try to source materials first from this land, and if not from there then we branch out to the forest reserve to harvest invasive species, or we branch out into the community to source reclaimed and used materials. I’m impressed with how thrifty and resourceful we all enjoy being, building from bamboo, weed-trees, tires, earth bags, and used metal containers, to old church doors, reclaimed cedar, redwood and stained glass. Some of us do it because we are frugal and others do it because it is fun and we enjoy the creative challenge. Some simply prefer the look and feel of used and/or raw materials from the land. We end up with stylish, unique, and frankly, beautiful homes, and I am happy that plywood has been kept to a minimum. The take-home point here is, we commit to this practice because it is ecologically important not to rely on new, and imported materials.

Walking out past the humming honeybee yard, beyond the orchards and pastures, tucked in on the secluded edge of the wild, we built a special, unobtrusive, circular structure for our council-space, our maloka. This place, built of natural materials and borrowing from traditional South American and Hawaiian cultural design, stands ready for intimate gatherings, celebrations, meetings, and ceremonies. Its location is perfect for sound autonomy and is truly a peaceful, meditative, and healing place.

We have 3-4 communal lunches or dinners per week at our common kitchen. We use as much food sourced from the land as possible for these meals. Tonight is my night to prepare dinner with two others so I’ll need to remember to pick a basket of chaya greens on the way back up from my cottage. We’ll be cooking one batch in wild pig bone broth and another batch in fresh coconut milk. A fresh, colorful salad from the garden with avocado will provide a crisp, raw addition to one’s plate of food. Since we are out of our solar-dehydrated breadfruit flour I plan to make flatbread from one of our other homemade flours–plantain or cassava. The main dish will be fried tilapia from our aquaponic system; for the vegetarians, stir-fried “rice” with perennial lima beans, pigeon peas, wild fern fiddleheads, and moringa in riced breadfruit. We’ll be using imported cold-pressed coconut oil to fry the fish—our Samoan and local coconut plantings are just starting to produce and the harvest so far have gone to coconut water, spoon meat, and coconut cream. But we’ll solve the oil challenge in the next few years. The meal will be rounded out with a ferment: chayote-chinese cabbage kimchi, made with ginger, turmeric, Hawaiian bird peppers and the sea salt we harvested and dried from one of our coastal outings. We’ve got ample sinks and drying racks for everyone to efficiently clean their own dishes, so my work is basically done once the meal is served!

Following our community meals, someone often takes the opportunity to host a movie night, a music night, a puppet show or some kind of entertainment, in the adjacent comfy community lounge. Sometimes people come up with performances, other times we have talent shows, sometimes there are story-telling sessions. Sometimes we keep it simple and sit around the fire and talk. No one has to stay for these events but more often than not we have a full house. On non-meal nights, the space is sometimes scheduled for a more serious focus, like the New Paradigm Studies or Radical Feminism courses currently ongoing. There are also unscheduled evenings in the lounge and they’ve led to some of the funnest impromptu gatherings. We like each other and spend plenty of time together as a community.

Don’t get me wrong, it isn’t all sunshine and rainbows. You can’t hide in community; patterns of avoidance, co-dependence, blame/victim-hood, etc, come to the surface. That’s why we worked hard to ensure our members were emotionally mature and ready to take responsibility for their actions and feelings. This foundation creates a whole different spirit of interrelating than what most of us grew up with, or than the culture at large. And when compassionate, gentle, and firm attention is given to someone who genuinely wants to change, a flowering can happen that is beautiful to behold.

Of course we all continue to need to work on ourselves because stuff comes up regularly. That’s what the weekly Heart-Share is about–learning to confront a person or be confronted with valuable, growthful, feedback. It brings up all kinds of feelings of embarrassment, shame, or inadequacy. Ultimately the vulnerability brings us closer and helps us empathize with each side of a conflict. It allows us to see a more complete story. In the end, we see how deeply similar we are, in both our nature and our neuroses.

Thank goodness we were wise enough to set our community up so that genuine equal accessibility to resources and decision-making is guaranteed for every member. Our clear, written-out, and signed membership procedure and agreements also do a lot to help with conflict. Ultimately, these agreements serve as our ‘code of conduct,’ and every member is responsible for living up to them. Of course, each of us falls short in some way, at some time. To work through these times of ‘stuckness,’ we have a lot of tools at our disposal; some of us have gone out to trainings to learn, and return ready to teach the rest of us. We have learned experiential, body-oriented forms of processing conflict that are more heart-centered than heady. It takes regular practice to integrate these new tools and sometimes this can be frustrating, but ultimately, having a variety of communication and counseling styles/modalities helps a broader range of people and issues we deal with in community.

Communal living requires work of the heart, no doubt, but work on the land is vital to the heart of the systems here. The benefit of living with many others is that the work gets done with a fair amount of efficiency. “Land-dances”, to borrow a term passed on to us by one of our well-seasoned community members, are weekly work-parties where most of our members, along with interns work together for several hours of the day. This week, we’ll be continuing a selective hand-clearing of waiawi guava on three acres that’s being gradually transformed. We use hand-saws and loppers to break these “feed” trees down into mulch piles and firewood for our rocket stoves. We’re finally getting around to planting a genuine food forest in the area, leaving enough guava to provide shade for the grafted and seedling durian, avocado, and jackfruit trees to get started without too much weed competition. Our interns help out a lot and seem to really enjoy the learning that happens here.

Aside from having several common areas, we have intern cabins and of course we each have our own homes. I have a shared living space with my partner and we also each have separate spaces to be our offices/studio spaces. We have pull out sofas in these spaces for guests to come stay. There are numerous communal composting toilets we share between a few houses. We also have communal showers. Many of us have kitchenettes at our places for those days we don’t have communal meals; some use the common house for all their meals.

We have a bicycle-powered laundromat on the land. We found 4 discarded washing machines with burned out motors and converted them so that pedaling a stationary bike drives the motor. We’re so happy with our design that we are now working with the County Solid Waste Transfer Division to divert the stream of dumped washing machines and bicycles to a new start-up machine shop that will get our designs into wider use. Our community’s dryer is a well ventilated greenhouse space that generates ample heat and convection. On a sunny day your clothes can dry on the line in an hour! There are plenty of lines for everyone in this indoor space but we also have outdoor lines as well. Currently we are working on many projects based on drive-band technologies and wheels.

We already utilize solar ovens, parabolic cookers, rocket stoves, as well as dehydrators to cook and process foods; and we utilize passive solar for heating hot water mostly, but on those days of rain and gray, it’d be nice to have hot water for washing. So we are working on a biodigestor to provide both alternative cooking fuel, and fuel for on-demand hot water.

We have a school program for the kids on the land as well as other kids in the neighborhood who want to attend. Classes happen 3 days a week and there are a handful of folks who run the school while the rest of us pop in at various times to contribute when kids want to learn particular topics. No one has to attend any classes—rather kids gravitate towards the various focuses according to affinity and attraction. All ages are welcome at most classes. The school’s democratic “awareness” system is a wonderful training for kids about the responsibility that comes with academic freedom. On school days it is fun to have a bunch of kid energy around. There are plenty of teaching moments and good opportunities for socializing with various aged kids.

We raise chickens, ducks, guinea pigs, tilapia, sheep, and pigs. I’d like us to get a small horse, a donkey and perhaps have them make a mule together. We can train them as work and pack animals on the land as well as for transportation to town. We will have to see if the land can support more animals.

We finally slimmed down to three cooperatively owned vehicles: two cars and 1 truck. If you need a car you sign one out or reserve one ahead of time. The renter of the car pays the designated fee per mile, to cover gas and repairs. Those folks who take a car often run errands for community members while they are out. Maybe individuals don’t have the autonomy and freedom they once had with this system, but for the small sacrifice of having to plan your trips better there is a far greater gain–more cooperation, less fossil fuel use, and way less expense! In the near future, fossil fuels are likely to dwindle and become too expensive a commodity to power individual cars. We will likely have to switch to riding large public buses, riding bikes, and riding horseback. That’s why investing now in training pack and work animals might be wise. Our community members know the realities of our planet so we are designing for a post fossil fuel world.

People here live in various configurations from individuals, to traditional, poly, or extended families. Each person, including children, holds responsibility for the consequence of their actions/interactions. Housing is as varied as the people– some of us went modular and built multiple tiny homes, while others built one bigger space with everything under one roof. Our housing units and the surrounding zone 1 around the units are where we have autonomy over our own spaces but beyond that we share everything including several common buildings. I enjoy having autonomy over our kitchen garden space and having roosters and chickens be far enough from my house to not have their noises disturb the peace around the house.

We have a duplex that we try to keep vacant for visiting relatives and friends (of course, some members prefer to host relatives in their own homes). Everyone does their best to extend courtesy and friendliness to members’ families when they arrive, and most of those relatives are flexible and of an amiable disposition. It can be difficult when the odd scampering naked child or overheard swear word—occurrences that are a regular part of our culture—causes offence to a visitor. But these kinds of culture clashes can happen outside of community, too.

I have a couple of really close friends in the community (my besties), and a community of friends in the extended neighborhood. So I have plenty of opportunities for social experiences both on the land and off. Occasionally, a group of us will go on a camping trip—to Ho`okena or Keanakolu. Or, there are events like the `Aina Fest and ManaFest that we like to attend as a community, taking turns staffing our nonprofit’s simple-living booth. But, as I look back on my life, I see that so many of the needs that I used to go “out there” to meet are now met “in here” among my community family of friends. I think this is more like how we originally lived as humans, and much of what passes for socializing and entertainment these days is just to compensate for our fairly isolated and limited individual and nuclear family lives. Creativity and hand-work have been replaced by mass-produced objects and the illusion of choice. I cannot judge anyone caught up in this system because it is ubiquitous and challenging to escape it. But it is likely that as things collapse, people will begin to forge community because we are social beings who need one another. I’m just glad to have already found my place in one!